I've been deep in the trenches with a few new projects lately and noticed something interesting about my current works in progress. My characters are becoming more flawed and messier with every book I write. But they also feel more human. My favorite way to write romance is to wedge an aggressive sense of humanity into a premise that sounds like a modern fairy tale. My happy endings have become roadmaps for healing from wounds that seem permanent.

It’s okay if you struggle with liking my characters at first glance. Trust me, they don't like themselves either, at least not at the beginning of their journey. I write characters I wouldn't want to hang out with until they've completed their growth arc. Flaws are evidence of our humanity. Perfection is for robots.

But have you ever found yourself reading a romance or watching a rom-com and thinking, "This character doesn't deserve the love they're being offered"? I catch myself doing this sometimes, and it always makes me pause. What am I really saying? That love is action and these characters haven’t done enough? Maybe. But sometimes I’m criticizing who the character is at their core, which feels a little gross. It implies certain types of people are undeserving of love. That kind of thinking makes it difficult for people to believe a happy ending between two disabled people or two poor people. How could two Black characters possibly be happy when Jim Crow was a thing? See where I’m going with this? To say a character doesn’t deserve to be loved is loaded in ways I don’t think we always see. So I decided to pick at my own criticism and uncover what was happening underneath.

Fiction is a lie used to tell a deeper truth. Sometimes my reactions to a character aren't really about the character at all. It’s about what this particular character construction communicates about how the world works. There’s a disconnect with the author’s thematic argument.

A thematic argument functions as the universal truth your story ultimately embraces. This is often the answer to that “so what?” question, we usually see in craft books. What’s the point of your story? What is it saying? In genre romance, the broad answer is "Love is the key to happiness." (I will repeat this until my dying breath. If your book isn't arguing this point, it's not a romance.) Love interests must embody this theme in some fashion, or they aren't fulfilling their essential narrative purpose. (In a romance, both characters are each other’s love interests, even if it’s a single point of view. If Sally isn’t bringing anything to the table, we will root for Jack to take his grand gesture elsewhere.)

This also helps explain why a romance in which the couple doesn't end up together simply isn't functioning as a genre romance. That kind of story inevitably makes a fundamentally different thematic argument. (Consider how Wuthering Heights, despite its passion and intensity, ultimately argues that unchecked desire can destroy rather than heal—the opposite of what romance promises.)

This requirement creates a narrative tightrope for writers: a love interest must be flawed enough to have a meaningful journey, yet must simultaneously represent someone's believable happy ending. They must embody the promise that love offers a path to wholeness while remaining human enough to avoid becoming merely a wish-fulfillment cutout with perfect abs and no personality.

Let’s Do Romance Math!

A compelling main character drives the story. They typically begin in a state of lack or imbalance and gradually journey toward wholeness. Their choices, especially their mistakes and missteps, propel the plot forward. Their flaws aren't random personality quirks designed to make them edgy or relatable, but function as load-bearing walls in the story's architectural structure. Someone without issues or conflicts would solve their plot problems immediately, and then we'd have no story worth telling.

In contrast, a love interest exists primarily in relation to the main character's journey. They represent something essential that the protagonist needs—not just companionship or a warm body, but a living embodiment of the thematic truth the story ultimately wants to convey.

And herein lies the struggle: real people don't "embody" abstract concepts. If like me, you’re drawn to characters that make you want to throw the book at the wall, you might struggle to balance these competing demands.

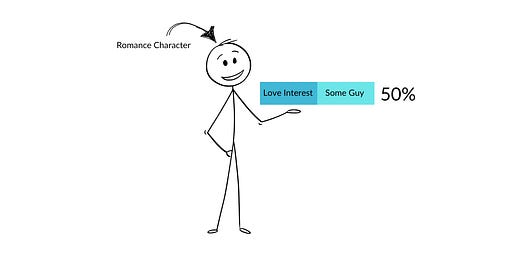

I've started thinking about characters in terms of percentages:

In fantasy with romantic elements, the split might be 80/20 character/love interest

In literary fiction with a romantic subplot, perhaps 90/10 character/love interest

In genre romance, character roles might split 50/50 between main character and love interest functions

Looking back, I feel like The Art of Scandal landed around 60/40, with character development slightly outweighing the love interest function. Nathan is fundamentally kind but persistently insecure, which has trapped him in a form of new adult stasis. Rachel is impulsive, often cynical, and defensively cold when confronted with anything that makes her feel vulnerable. She's caught in a shame spiral stemming from past mistakes that trapped her in a marriage that hollowed her out.

But Nathan also has a transformative effect on Rachel. When she's with him, she becomes her most authentic self, the person she could be if her past didn't trap her. He's thoughtful and generous, blazingly hot and spectacular in bed. When they're together, readers glimpse who Rachel could become if she finally embraced the fundamental truth that love, not status or security, will make her truly happy.

Rachel has the same effect on Nathan. She makes him want more for himself and, crucially, believe he can achieve it. Both characters propel the plot through their internal journeys and struggles. But these separate paths directly impact and intertwine with the central romantic plot, gradually moving them closer to realizing that essential thematic truth: that love, messy and complicated as it may be, is ultimately the answer they've both sought.

With August Lane, I pushed the balance even further out of whack, probably 70/30 if I’m being honest with myself. And my current work-in-progress is even worse (don’t ask). But all of these books make that core thematic argument that love is the key to happiness. The plot remains anchored by the relationship at its center. The couple ends up together (that's not a spoiler, by the way—it's about as surprising as the detective solving the case in a murder mystery). So despite their strong main character energy, I think they’re doing their job as a love interest.

Making it Work

Let’s go back to me thinking that character doesn’t “deserve” their love interest. What I’m really saying is that this character doesn't sufficiently embody the core premise the book is attempting to sell. In other words, they're not doing enough of that essential love interest work to balance their messy human qualities.

Try checking the math if you feel this way about a character in a book you're reading. How much of this character seems to function primarily as a love interest versus a realistic, flawed human being with significant growth still to accomplish? Understanding this balance might help contextualize your reaction.

Second, if you're writing romance, pay close attention to who your characters become in scenes together. A well-crafted love interest should consistently bring out the best in their partner, even when conflict arises. The theme of "love is the key to happiness" doesn’t have to be told to the reader through exposition or dialogue. It can be shown organically through the transformative effect these characters have on each other. Whenever these two people come together, they should become the smarter, funnier, more authentic humans they have the potential to be once they fully grow and embrace love. If your character doesn't have this elevating effect on their partner, they're not successfully doing the love interest work, regardless of how your percentage math might break down on paper.

Words Worth Keeping

He puts his things down and kneels by the bed like he's saying a prayer. He takes my hands and kisses me, again and again, with those ridiculously soft, full lips. And I see him, all at once, the man and the boy, the lover and the beloved.

– Tanked by Mia Hopkins

Mia Hopkins does amazing character work in her Eastside Brewery series. The characters are flawed and compelling, while embodying the healing potential of love that makes a strong love interest. In this gorgeously written quote, one of the main characters is seen by his love interest as complete and in progress, both the fulfillment of a promise and a human still on their journey. It’s a balance I strive for in everything I write.

Have you ever put down a book or disliked a romantic movie because you felt deep down that a character simply didn't "deserve" their happy ending? Writers, have you ever done this kind of math when developing characters? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

It’s been a while since I mentioned preorders, but they’re so important for authors! If you plan to read August Lane, please consider ordering in advance. Preorders tell bookstores and publishers you want to see more of what you’re buying and they’ll ensure my messy WIPs have a publishing house to call home. I’ll be announcing a really cool preorder thank you gift soon.

If you don’t want to commit to something you can’t hold in your hands until July, request the book at your local library! Mention the book to friends! Add it to GoodReads and Storygraph. If you read it early, leave a review! Everything helps.

Love this analysis! There's a fine line between "You deserve each other" (sincere) and "You deserve each other" (sarcastic). Which is why I think enemies-to-lovers is the BEST lol

I love this idea of romance math -- brilliant! And you're so right that the question of "does this character deserve love" gets loaded real fast, but is also worth considering from a craft perspective of just like, what are you putting on the page, what are your intentions, how are you hoping it will be received, is there a gap between that, etc.?